Case Study | Medication Error Sparks Innovation

In many hospital pharmacies today, the pace is hurried. Staff rush to fulfill complex orders for waiting providers with patients’ health dependent on their accuracy. With so many urgent patient needs, staff changes, increasingly complex medications, direct patient care responsibilities and the inevitable influx of new team members who need to be mentored and trained — all in the setting of evolving federal and state medication regulations — how can a pharmacy team prevent errors before they’re passed on to patients?

At Virginia Mason, an error occurred in the pharmacy years ago that had a profound effect on a patient, leaders and staff — and eventually the processes the pharmacy team used to move forward and prevent the recurrence of that error. How did the team uncover the systemic cause of the problem, and how did they dramatically reduce defects in the process to make sure such an event never happened again?

Discovering an unforeseen error

In the hospital’s sterile compounding room, a solution that was prepared for a patient was incorrectly prepared. It should have been made with infliximab, an immunomodulating agent used to treat the pain of rheumatoid arthritis. Instead, the solution was accidentally prepared with etoposide, an antineoplastic with known side effects including gastrointestinal problems, weakness, hair loss and more. (Details in this article identifying the event and the patient have been changed to protect the patient’s privacy.) The compounded medication was sent to the patient’s nurse, with permission to fast-track the infusion for the patient, who had tolerated the treatment of the prescribed medication well in the past. By the time the pharmacy team discovered the error, the full infusion had already been administered.

What the pharmacy team did in the short-term and the long-term, and what they’ve continued doing today, has resulted in a measurable improvement in safety, quality, efficiency and team dynamics.

Reporting and analyzing the error

The staff member who discovered the error immediately called-in a Patient Safety Alert System (PSA)™, which actively notified Virginia Mason’s patient safety team to act quickly on any threat or incident of patient harm.¹ The PSA team and operational leaders mobilized immediately to uncover exactly what had happened.

Roger Woolf, the administrative director of pharmaceutical services, was responsible for talking with the patient. “The patient was very upset,” he said. “He wanted to know how we had allowed this to happen, how much harm the drug would cause him and how we would prevent the same type of error from happening to others.”

Woolf, frontline staff and the PSA team went to work. They found that because it was a Saturday, the preparation had been compounded in an area that was different than the area usually used by the staff members who worked Monday through Friday. Additionally, the Saturday staff did not have as much experience or training as the weekday team.

But the team didn’t just chalk up the error to an inexperienced staff member who should have known better or who wasn’t properly trained. They knew that the hospital already had system checks in place to prevent such an error from happening, and all staff members had abided by these checks for years, keeping their patients safe. They dug deeper, using the lean method of root-cause analysis to find out how their system could have allowed a human error to find its way to a patient.

In the subsequent report, the team concluded that the primary source of the error was the misidentification of the product when preparing the infusion. The pharmacy technician had used a 1,000-mg vial of etoposide to prepare the dose instead of the intended 100-mg vial of infliximab as noted on the label. In keeping with the process, the technician had placed the prepared product, the vial used in preparation and the syringes used to withdraw the saline at the specified location for the pharmacist’s final check, which was the standard procedure for all batched compounded intravenous products

At this point the pharmacist reviewed the product label, noted the dose and validated the dose but did not catch that the incorrect drug had been used to prepare the infusion. Then, the infusion bag was delivered to the patient’s providers. The nurse in charge of administering the drug validated the infusion labeling against the physician’s order and administered it using the standard procedures for infliximab.

Creating a short-term solution

Although the pharmacy team was already working on a long-term solution to prevent this type of error from happening again, the board wanted a short-term solution implemented as soon as possible.

In keeping with the Toyota Production System’s practice of slowing down a process, or “stopping the line,” after an andon is pulled at the factory, the team slowed the sterile compounding process so that no employee was permitted to batch the ingredients to make an infusion.³ Every intravenous medication order was to be filled using one-piece flow — that is, one bottle and one label, for one patient at a time. Even if a technician needed to prepare several orders for a single patient, batching was no longer permitted in this modified system.

A long-term solution to keep patients safe

Slowing down the process was not popular among the staff of skilled pharmacists and technicians — after all, they already had what they thought was an efficient process, with conscientious employees, that had kept tens of thousands of patients safe for years. But they realized there was a safety gap that they’d never seen before — a procedural error that exposed a vulnerability in their process — and they were motivated to create a better system together to further strengthen the safety and reliability of the medication preparation process. In their subsequent improvement events, known at the organization as kaizen events, and during the testing of their innovative ideas, the team used four elements of mistake-proofing:

Inspection: The team developed standard work and tested new inspection steps to keep patients safe in the sterile compounding process, including a technician or pharmacist successive check after a product is drawn up into syringes but before it is admixed in an infusion bag. This includes reviewing pulled-back syringes for volume, medication and dose double-checks, as outlined in the Institute for Safe Medication Practice guidelines.⁴ Revisions were also made to the post-check pharmacist process to include the provision of all supplies used (such as the filters and labeled syringes) as well as the labeled final products.

Visual Controls: The team labeled and pulled back syringes to indicate the volume of the drug to be injected, created a quiet zone to allow pharmacists and technicians to focus during complex preparations, and created external setups for weekend infusions, such as bagging drugs and labeling preparations for individual patients, to simplify the preparations. The team also used the principles of 5S (Sort, Simplify, Sweep, Standardize, Self-Discipline) to standardize the IV room’s compounding hood, which they set up in a U-shaped format to best comply with regulations and ensure a safe compounded product.

Standard Work: The team created and tested written processes that clearly described key inspection steps and the layout of the sterile compounding workspace. They also modified the production of medication infusions so that the process eliminated multitasking and instead adhered to the ideal of one-piece flow, a concept proven to reduce errors.⁵ Staff schedules were revised to ensure the presence of the best-trained staff at all times.

Devices: The team knew that the right devices could further their mistake-proofing goals, so they set out on a learning journey to find what would work best. Team members toured and contacted other hospital pharmacies, and they researched numerous vendors to look into new technologies. To their surprise, there was nothing on the market that would help their team adequately prevent errors in the preparation phase without batching. Vendors told them the technology they wanted was years away, at best.

But the team didn’t give up. They knew they had a duty to Virginia Mason’s model of continuous improvement in their pharmacy, and there was more work to do.

Developing a bar-code scanning system

At Virginia Mason, innovation on all teams is encouraged. Ryan Tran, an employee who began his career at Virginia Mason as a pharmacy technician and is today a senior system engineer, took the lead on developing the medication bar code scanning system. Passionate about informatics, he and the other members of his team wanted to build a system that would catch all errors — the “perfect mousetrap,” as the team called it — to prevent any error in any stage of the process. But when the timeline started getting stretched, they decided to build it in stages.

“The team wanted to build the perfect system, and knew the implementation would be years away,” said Woolf. “So the leaders had to work with the team to reframe our goal, realizing we had to do everything we could to make it better now so that we could keep improving it incrementally. We had to do it for our patients.”

The unique ScanTran system, named for Ryan Tran, is high-functioning, using one-piece flow instead of batching. When a provider’s order for a patient comes in, a pharmacist verifies the order and generates a label. Then, a technician selects the drug based on the label and places it in the preparation bin. Next, the technician obtains the solution to be used in the preparation and places it in the bin. Then the technician scans the label, and then the drug and the solution, to ensure accuracy. When a defect has occurred, an alert will stop the process. Then, the technical staff member, who has been trained in rigorous standard work processes and has demonstrated his or her competency, prepares the sterile medication. In the final check, a pharmacist uses standard work to ensure that the right patient is receiving the right medication at the right dose.

The use of three checks, two by the technician and one by the pharmacist, was critical. At the same time the ScanTran system was introduced, the team installed cameras. The cameras have not only reinforced standard work, but they have provided a method for a retrospective review of process, which helps with feedback and training.

The results

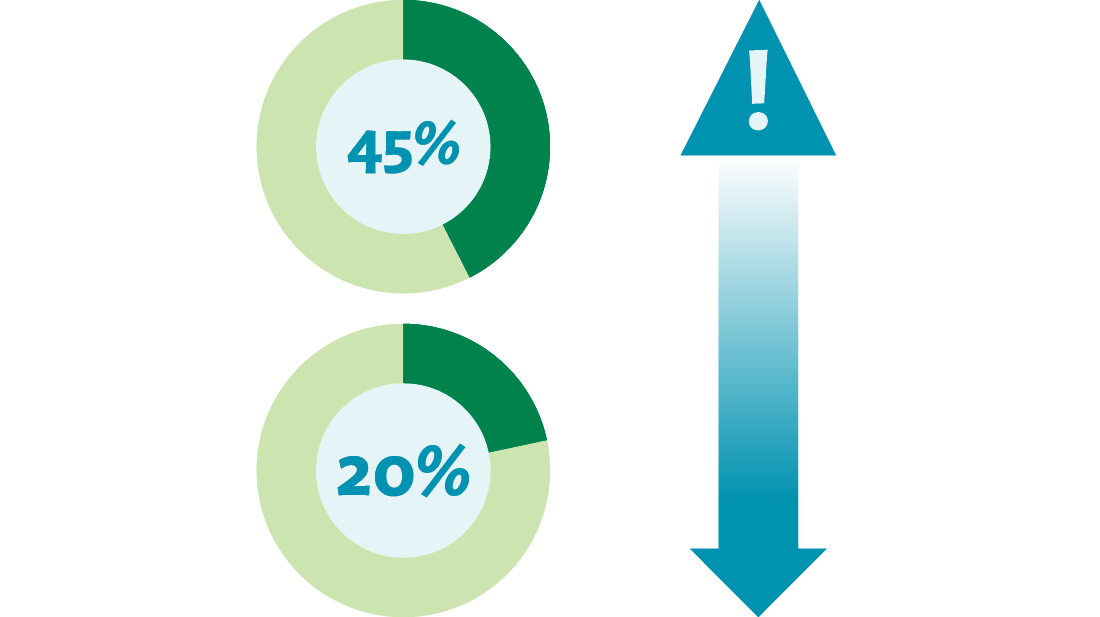

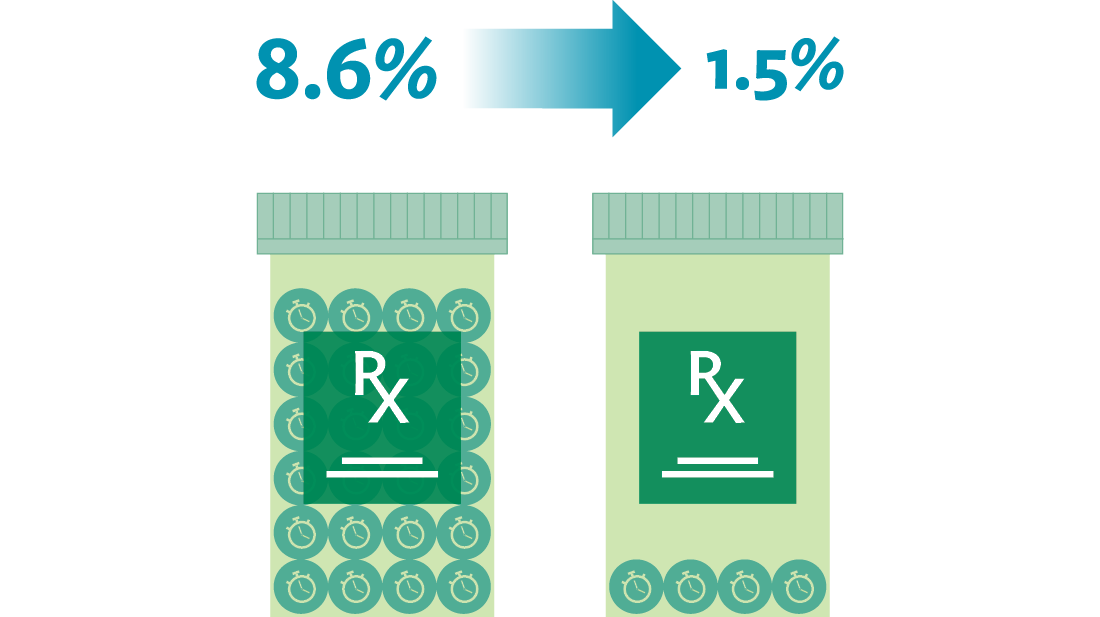

Through the implementation of mistake-proofing countermeasures, the team achieved a decrease in distractions and interruptions during medication preparation, from 45 percent to 20 percent. Through the same efforts, the team decreased the number of wrong preparation techniques, from 1.4 percent to 0.2 percent. The team also reduced the number of times they didn’t meet their goals for timely medication delivery to the patient, from an 8.6 percent incidence to 1.5 percent.

On an ongoing basis, the sterile compounding process is analyzed for improvement opportunities to ensure it is continually improving and moving toward delivering a defect-free product.

Why the team succeeded

It would be too easy to say that an error caused a hospital pharmacy to automate a new process to help them prevent medication errors. The real story is that a serious adverse event occurred to a patient, a concerned team of leaders and staff came together to solve the problem, and the team created a system — not to mention a functional technology — to make their sterile processing incrementally safer every day. What made this possible?

A culture of safety permeates the organization. After the error was discovered, the staff immediately used the Patient Safety Alert System, which immediately mobilized their patient safety colleagues to act.⁶ In a short time, the highest levels of the organization were notified, including board members, and the pharmacy leaders and staff were on the front line to analyze the situation and communicate directly with the patient. In Virginia Mason’s culture, the system — not an individual — is to blame for errors, and leaders and staff know that they need to work together to made the system safer and better.

The organization has an unrelenting focus on the patient. When Woolf talked with the patient, he learned not only that the patient was upset about the error and worried about the effects of the medication, but that now the patient might be too sick to travel to his son’s graduation, something he’d been looking forward to for a long time. Woolf met with his staff and told them the patient’s story. But he sensed that the staff didn’t feel strongly connected to the patient’s anger, worries and sadness brought on by the medication error.

“I was afraid that some of the staff had forgotten there was a patient at the end of their process, that the work wasn’t just about vials, stickers and bags,” Wolf said. And to bring his point home, he hung a photo of the patient on the pharmacy wall, where nobody could miss seeing it day after day.

The photo stayed up for years. When staff members asked when he was going to finally take the photo down, he told them, “I’ll take it down when every member of the team understands the connection of what we do to what the patient experiences.” And in keeping with the improvement work happening every day at Virginia Mason, the team makes sure that their patients’ point of view is always strongly represented in the team’s kaizen events to improve the safety and efficiency of their processes.

The focus for the team was, and is today, how the whole system works for the benefit of the patient, not how the technology can help the staff do their tasks more quickly.

Leaders and staff are committed to safety, quality and efficiency. Using lean methods and tools, the leaders worked with staff to generate ideas, create standard work, test the process and implement the process. They used the four levels of mistake-proofing to keep them on track, they conducted research and generated new ideas, and they trained using the Training Within Industry (TWI) method so that each team member was expertly trained.⁷

They also understand how their work connects to the patients they serve every day.

“We know how dangerous compounded IV medications can be when mistakes are made, and that motivated us to build Virginia Mason’s ScanTran system,” says Tran. “Now we’re able to detect errors before they reach the patient.”

Today and the future

Just as Virginia Mason’s pharmacy team members visited other organizations for inspiration on their patient safety journey, today pharmacists and leaders from all over the world tour Virginia Mason’s pharmacy.

Years later, the team is still working on improvements, as part of their commitment to incremental improvement. “Our long-term vision for safe, sterile medication processes is zero defects,” says Woolf. “We’re measuring our results and always looking for ways to make our processes efficient and error-proof.”

Originally published May 26, 2016, updated September 16, 2022

References

2. Kenney C. A Leadership Journey in Health Care: Virginia Mason’s Story. New York: CRC Press; 2015.

3. McIntyre M. How can andons improve patient safety? https://virginiamasoninstitute.org/how-can-andons-improve-patient-safety/. Virginia Mason Institute website. Published February 17, 2016. Accessed October 5, 2016.

4. Institute for Safe Medication Practices. Guidelines for SAFE Preparation of Sterile Compounds. Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP). 2013. https://www.ismp.org/tools/

guidelines/IVSummit/IVCGuidelines.pdf. Accessed October 5, 2016.

5. Virginia Mason Institute. Getting closer to continuous flow in health care. https://virginiamasoninstitute.org/getting-closer-to-continuous-flow-in-health-care/. Virginia Mason Institute website. Published March 16, 2016. Accessed October 5, 2016.

6. Virginia Mason Institute. Patient Safety Alert System stands the test of time. https://virginiamasoninstitute.org/resource/embedding-a-system-to-protect-patient-safety/. Virginia Mason Institute website. Published September 4, 2015. Accessed October 5, 2016.

7. Graupp P, Purrier M. Getting Standard Work in Health Care: Using TWI to Create a Foundation for Quality Care. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2012.